Floralie Resa

Translation from « Architecture de la biphobie » published originally the 16th of January 2025.

Summary

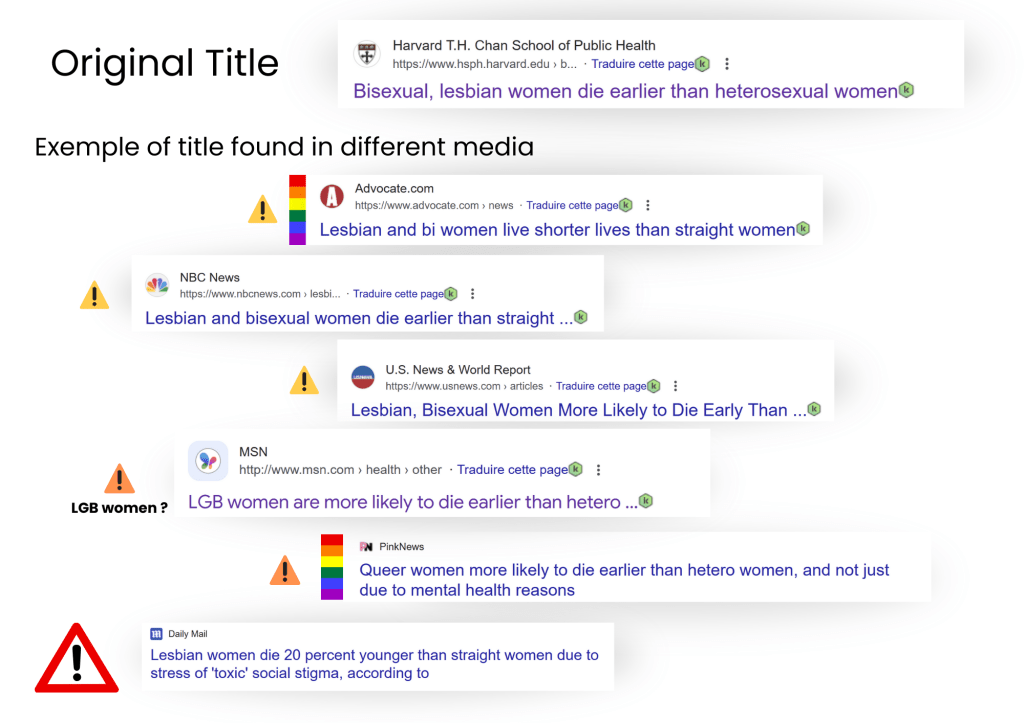

Theoretical essay on the origins and manifestations of systemic biphobia. In contrast to the ideas developed by Eisner, it situates biphobia as an autonomous product of homophobia rather than of sexism, and proposes a new theoretical framework supported by case studies and statistics. Ranging from domestic violence to media coverage of studies on the excess mortality of bisexual women compared to lesbian and heterosexual women, this report offers a simple structure for understanding the difference between homophobia and biphobia in a historical and international context.

Preamble

The theorization of biphobia is sparse and often confined to accounts of everyday microaggressions: a guy asked me for a threesome, someone claimed bisexuality doesn’t exist, or a lesbian was mean to me. This lack of depth, in my view, stems from the fact that bi people who are passionate about theory don’t spend enough time together for their ideas to mutually enrich one another.

In activist circles, we often underestimate the time and labor required to develop the theoretical frameworks that help us understand oppression. We read books on these topics, we discuss them, and we overlook how much time, reflection, and collective dialogue was necessary for these concepts to be rendered clear. Theorization, including that of biphobia, relies on collective intellectual labor.

I conducted research in the experimental sciences for several years and witnessed how flashes of insight and fleeting inspirations emerge from exchange and dialogue among specialists. We talk constantly, read each other’s work, experiment on our own, excited to share results, and we debate. Long before a theory is proven, it must first be imagined and tested. Theory-building happens collectively, through real-life discussion or through reading and drawing inspiration from others’ work. Our ideas bounce off one another, growing richer in the process.

So, before proceeding any further, I would like to acknowledge the bi individuals whose ideas have resonated with mine, whether directly or through their writings, or who have enabled my own theorization by offering time and attentive listening. Within my circle of bi and pan friends, there is Eliot Astree, Axiel Cazeneuve, and Precarité Inclusive, known as Préca. Eliot and Axiel are my comrades-in-arms. We have written and spoken so much together that whatever the topic, if I become interested in an idea, they inevitably hear about it. Préca is as passionate as I am about bisexuality, and we have had extensive debates on these subjects.

On the theoretical front, I must highlight the influence of Stéphanie Ouillon (Wohosheni), Julia Shaw, and Autumn Bermea. Stéphanie Ouillon is an engineer and independent researcher on the history of bisexuality as it relates to French gay activism. Julia Shaw, a German criminologist, has made accessible a significant body of research on bisexuality. Autumn Bermea is a clinical psychology researcher who co-authored one of the most important peer-reviewed articles on the violence experienced by bi women in their relationships. That article had a profound impact on my activism, as it gave me language to articulate the violence I had endured and opened my eyes to the effects of biphobia I had previously only witnessed.

My patrons and those who support my work on Instagram have also deeply motivated me to write and reflect. I am immensely grateful to them for the platform they have offered me.

I have an ambivalent relationship with the work of Shiri Eisner, whose writings I postponed reading until after most of my own had been completed. I came across fragments of her texts as bi activists shared her work. Yet I cannot deny the tremendous influence she has had on bi thought. As for Robyn Ochs and Julia Serano, they have deeply shaped my thinking, so embedded are their ideas in contemporary bi discourse. I simply did not know who they were or that they had authored so much of what is now considered mainstream. Robyn Ochs is a bi activist who has extensively theorized biphobia through the lens of invisibility. Julia Serano, a trans and bi activist, has written prolifically on binaries and bisexuality. Her influence on transfeminist thought often overshadows her contributions to bisexual theory, yet she remains a major theorist in that domain.

There are other names, now invisible, forgotten, that have also shaped bisexual thought.

It seemed essential to begin by recalling the collective nature of how bi thought has been built thus far, and the crucial role that the circulation of ideas has played. I have benefited from those who transmitted others’ ideas to me, and from those who shared my work. I would therefore like to end this preamble with a quote from a French lesbian speaker, Nathalie Sejan:

“We often feel powerless or useless in an age of virality and large-scale influence, but my experience is that consciously circulating the things we love and that matter to us is a powerful way to shape the tone of society and general trends. The world is a collective endeavor; circulation is an effective tool that all of us can use freely and continuously. So I circulate.”

Introduction

The term “homophobia” was not the one initially used when gay people began theorizing their oppression. Stéphanie Ouillon (Wohosheni), a specialist in the history of bisexuality in France who has worked extensively with 1970s archives from the Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire (FHAR), explains: “At that time, the word ‘homophobia’ didn’t yet exist in France. The expression ‘anti-homosexual racism’ was widely used instead” (Wohosheni 2024-a). To convey their experiences to the general public, it was easier to draw on the concept of an already recognized oppression such as racism, unlike homophobia, which had not yet benefited from the same history of activist analysis. It took years of intellectual and political labor to theorize what homophobia was, how it manifested, and how it affected homosexual people. Just as the term “homophobia” took years to gain public recognition, biphobia today faces similar, if not more complex, challenges.

The term “biphobia” is used by bisexual people to name their oppression. Today, while homophobia is widely recognized and understood as a real and systemic form of discrimination, biphobia is not. It remains poorly understood. Much like gay activists once struggled to articulate what has now become widely accepted knowledge, bisexual thinkers today are also working to define and theorize what biphobia actually is. What I have learned through bi activism is that speaking about biphobia often provokes highly defensive reactions within the LGBT community itself, as well as significant misunderstanding in the heterosexual majority. Why does biphobia remain so poorly understood and under-recognized, and how can we theorize this oppression in a way that is both specific and systemic?

This essay is structured in four parts in order to clarify the architecture of biphobia, its origins and its systemic manifestations. In the first part, I will summarize the current state of biphobia theorization and present the most prominent conceptual frameworks to date. In the second part, I will argue for what I believe to be the true origin of biphobia as a specific form of oppression and introduce a new theoretical framework that accounts for the social structures sustaining it. The third part will focus on distinguishing between lesbophobia and biphobia. Finally, in the fourth and last part, I will illustrate the most significant manifestations of systemic and institutional biphobia.

Part 1 – Where Does the Conceptualization of Biphobia Stand Today?

Several activists and intellectuals have contributed to the development of a bisexual understanding of biphobic oppression. Julia Serano defines biphobia as follows: “Often literally read as a “fear of” or “aversion to” bisexual people. I typically use the term in a broader manner to describe the belief or assumption that bisexuality is inferior to, or less legitimate than, monosexuality (i.e., being exclusively attracted to members of a single gender/sex)” (Serano 2016).

In this section, I will focus only on those theorists who have had the most significant impact within the bisexual community and whose work on the origins of biphobia has been the most widely circulated. The first person I will mention is Robyn Ochs.

1. Definitions ans Theoretical Contributions

Robyn Ochs : The Erasure of Bi People as an Accident of a Binary American Culture

Robyn Ochs is an American bisexual activist and author. She has written extensively on institutionalized biphobia, that is, biphobia that stems not from individuals, but from systemic structures. Ochs’s work has focused on biphobia as the erasure of bisexuality from both public and LGBT discourses (Ochs 1996). Her activism has centered on increasing bisexual visibility. She is the co-author of two major works on the subject: Getting Bi: Voices of Bisexuals Around the World (2005) and Recognize: The Voices of Bisexual Men (2014).

According to Ochs, bisexual erasure stems partly from monogamy and partly from a binary cultural framework. Bi people, often in monogamous relationships, are not immediately identifiable as bisexual, since they are seen with only one partner at a time. In an article published in the Huffington Post (Zane 2016), Ochs also argues that the United States’ deeply ingrained culture of binarity, reflected in everything from racial segregation to the two-party political system, contributes to biphobia.

Ochs is one of the most prolific and well-known bisexual activists, particularly recognized for her conceptualization of bisexuality. Her definition is frequently cited: “I call myself bisexual because I acknowledge that I have in myself the potential to be attracted–romantically and/or sexually–to people of more than one gender, not necessarily at the same time, in the same way, or to the same degree.” (Ochs, date unknown).

While Ochs has identified biphobia as present both within LGBT communities and broader society, she appears to attribute it largely to chance or cultural bias. Unlike Ochs, who interprets biphobia as a byproduct of binary cultural norms, Kenji Yoshino analyzes it as an intentional social mechanism.

Kenji Yoshino: The Erasure of Bisexuality as a Tool for Maintaining Norms

Kenji Yoshino is an American legal scholar and a gay man. He explored the mechanisms behind bisexual erasure in a legal article addressing U.S. sexual harassment jurisprudence. His article The Epistemic Contract of Bisexual Erasure, published in 2000, has had a major impact and has been cited over 700 times.

According to Yoshino, bisexual erasure is the result of a social contract between heterosexual and homosexual communities, both of which have shared interests in suppressing mentions of bisexuality. He identifies three motivations for this erasure: the stabilization of exclusive sexual orientation categories; the maintenance of sex as a “diacritical” axis (i.e., one that creates an unsolvable contradiction and serves to categorize humans into two distinct sexes); and the preservation of monogamous norms (Yoshino 2000). In short, biphobia, for Yoshino, fulfills a social need to stabilize human classification along both sexual and gendered lines, while reinforcing monogamy as a normative ideal. In this reading, bisexuality is framed as a disruptive force, an agent of transgression, that both heterosexuals and homosexuals seek to eliminate.

Yoshino’s vision of biphobia has had a profound influence on bisexual thought. Similar ideas appear in Michael Amherst’s 2018 work, where biphobia is described as a cultural fear of ambiguity and nonconformity, highlighting bisexuality’s inherent fluidity (Amherst 2018). Yoshino’s impact is particularly evident in the work of Shiri Eisner, an Israeli bisexual activist and writer. Eisner cites Yoshino’s arguments extensively in her book Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution (2013), and builds on them by framing biphobia as driven by the need to maintain binary systems and normative structures around monogamy and family.

Over a third of Eisner’s chapter Monosexism and Biphobia is devoted to summarizing Yoshino’s 2000 article, underscoring the central influence his analysis had on her thinking. Inspired by Yoshino’s work, Eisner goes a step further by proposing a broader structural framework that she terms monosexism.

Shiri Eisner: Monosexism as a Social Structure that Oppresses Bi People and Privileges Heterosexuals, Gays, and Lesbians

Shiri Eisner is one of the most well-known activist figures in bisexual movements, particularly due to her book Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution (2013). In it, she introduces the term monosexism to describe a patriarchal and colonial structure of oppression that, in her view, lies at the root of biphobia. Eisner popularized the use of the word monosexism, modeled on heterosexism, which has long been used to theorize the oppression of women and of gay and lesbian individuals.

In her book, Eisner strongly criticizes prevailing discourse within bisexual spaces, which she accuses of being overly liberal and focused on isolated, individual acts of oppression, rather than on systemic and structural dimensions. Through this critique, she highlights the lack of biphobia theorization in the early 2010s. While Yoshino’s work forms a major foundation of her thinking, she also cites several other key sources that help her articulate a more comprehensive analysis of biphobic oppression. Chief among these are Robyn Ochs’s work on prejudice and stereotypes about bisexuals, and the writings of Miguel Obradors-Campos, who applied Iris Marion Young’s theories of oppression to bisexuality.

Iris Marion Young, an American political theorist, characterized the oppressions experienced by minorities according to five axes: exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism, and violence. Obradors-Campos adapted these categories to the context of biphobia in a scholarly article (Obradors-Campos 2011), which Eisner then popularized in her book. As with Yoshino’s theory, Eisner devotes over a third of the chapter Monosexism and Biphobia to summarizing Obradors-Campos’s work, demonstrating its strong influence on her own theorization.

However, Eisner does not merely popularize existing theories; she also expands the field with her own original contribution: the concept of monosexual privilege. She proposes a list of privileges granted to people she terms monosexuals, that is, heterosexuals, gays, and lesbians. Among her list of 29 monosexual privileges are examples such as:

- “Society assures me that my sexual identity is real and that people like me exist.”

- “I feel welcomed at appropriate services or events that are segregated by sexual identity (for example, straight singles nights, gay community centers, or lesbian-only events).”

- “I do not need to worry about potential partners shifting instantly from amorous relations to disdain, humiliating treatment, or verbal or sexual violence because of my sexual identity.” (Eisner 2013)

In sum, Eisner has theorized the concept of monosexual privilege, coined and popularized the term monosexism, and helped disseminate and make accessible two major theoretical contributions to the understanding of biphobia: Yoshino’s epistemic contract and Obradors-Campos’s structural application of Young’s framework.

2. Quantifying the Effects and Establishing Scientific Consensus

Researching Biphobia: A Scientific Endeavor

The general public often minimizes the scientific legitimacy of the humanities. Yet the humanities are sciences, it is important to reiterate this. Theories about biphobia must be tested to be validated. While all theories on biphobia are grounded in argumentation, only some have been empirically verified.

For instance, certain theories proposed by Robyn Ochs have undergone scientific testing and validation. This includes her theory of double discrimination, wherein bisexual individuals experience stigma from both heterosexual and gay/lesbian communities. Empirical studies have confirmed the existence of such stigma coming from heterosexuals, as well as from gays and lesbians (Welzer-Lang 2008; Mulick & Wright 2002; Friedman et al., 2014; Hertlein et al., 2016).

It is easier to measure individual attitudes and quantifiable effects on bisexual people than to verify theories regarding the causes of biphobia. For example, researchers can conduct surveys to evaluate perceptions of bisexual people, establish biphobia scales, or measure indicators such as poverty, health outcomes, and experiences of violence. These scientific studies require substantial time and funding. The quantification of violence and harm experienced by bisexual individuals has been the result of a long academic endeavor, one involving tens of thousands of scholars, too numerous to name individually.

The current scientific consensus is clear: biphobia exists, and it has highly measurable effects on bi and pan individuals. However, progress in this research has long been hindered by the systemic exclusion of bisexual people.

For many years, bisexual individuals were not included in studies on gay and lesbian populations, reflecting the widespread belief that bisexual people did not experience discrimination in comparable ways. Later, through activism aimed at improving bisexual visibility, bisexual people were included in research, but not as a distinct category. It took years before bisexuals were studied in their own right. When they finally were, researchers uncovered a reality of violence that is almost unimaginable.

Across numerous indicators, bisexual people suffer significantly more than gay, lesbian, and heterosexual individuals. Bisexual women in particular experience higher rates of intimate partner violence, sexual assault, poverty, and poor health than any other group. The statistics on sexual violence are staggering. From adolescence, bisexual women are more likely to be raped and beaten up than both heterosexual and lesbian women (Bermea et al., 2017).

Before presenting these figures in detail, it is necessary to outline how research has been severely delayed by the exclusion of bisexual subjects and the denial of biphobia. Denying biphobia has not only impacted bisexual activists striving to defend their community, it has seriously hampered their ability to do so. What better way to ensure biphobia remains invisible than to prevent it from being studied in the first place?

The Exclusion of Bisexual People from Scientific Research

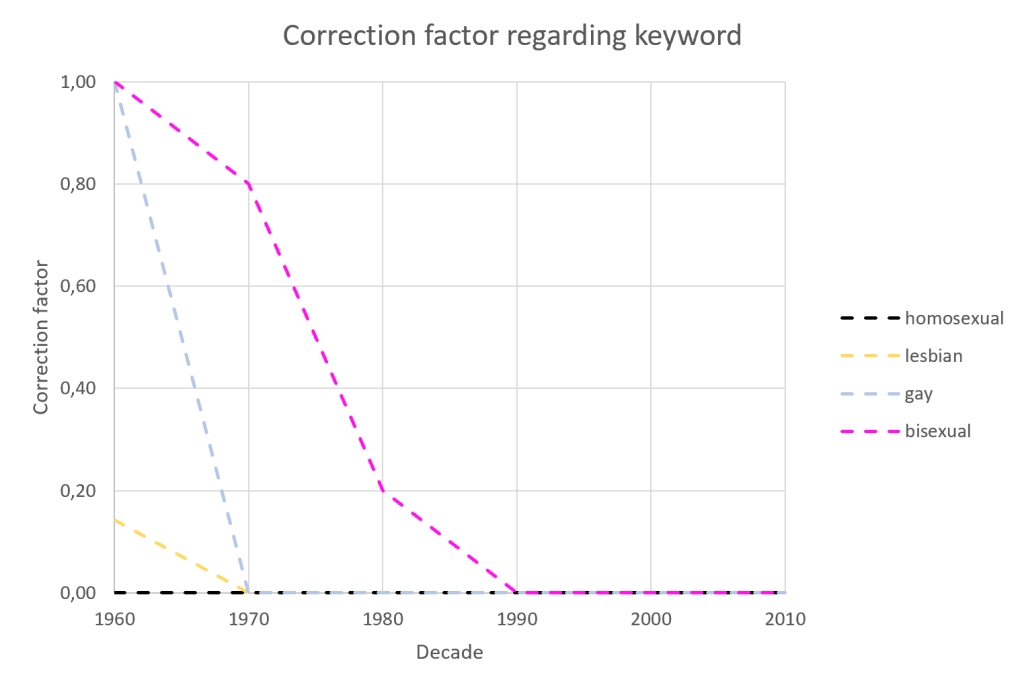

I observe three more or less distinct phases in the study of prejudice experienced by bisexual people:

- Exclusion (1960–1980): Research on sexual minorities does not mention bisexual people, focusing solely on gay men and lesbians.

- Token Inclusion (1980–2000): Bisexual individuals are included in studies, but not analyzed as a distinct group.

- Inclusion and Autonomy (2000–present): Bisexual people are both included and studied as a group separate from gays and lesbians.

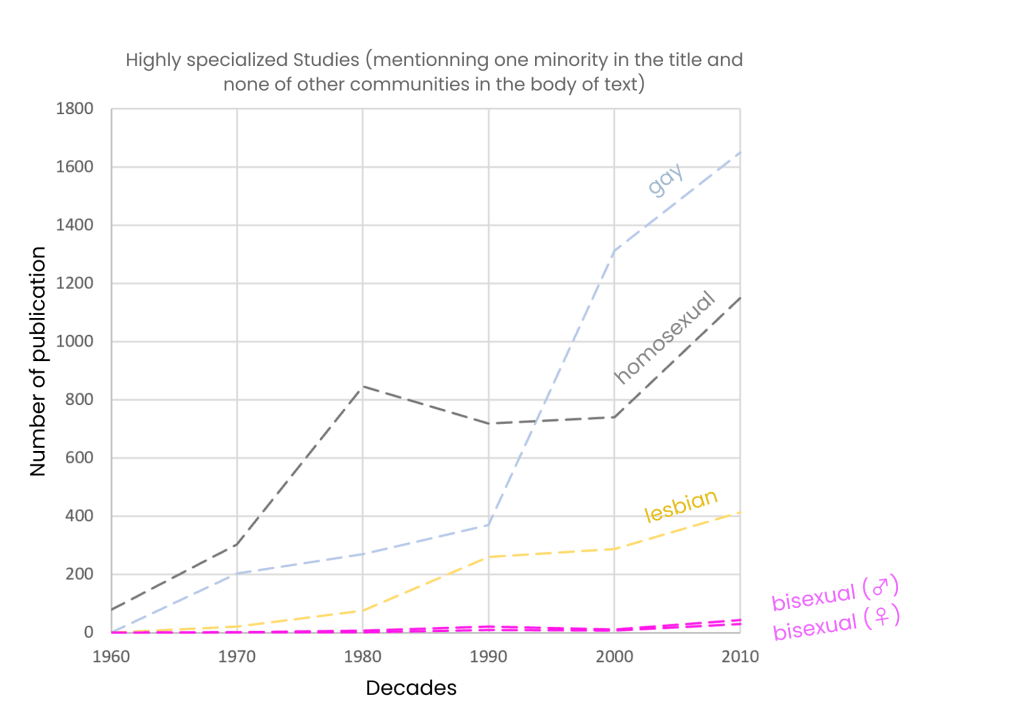

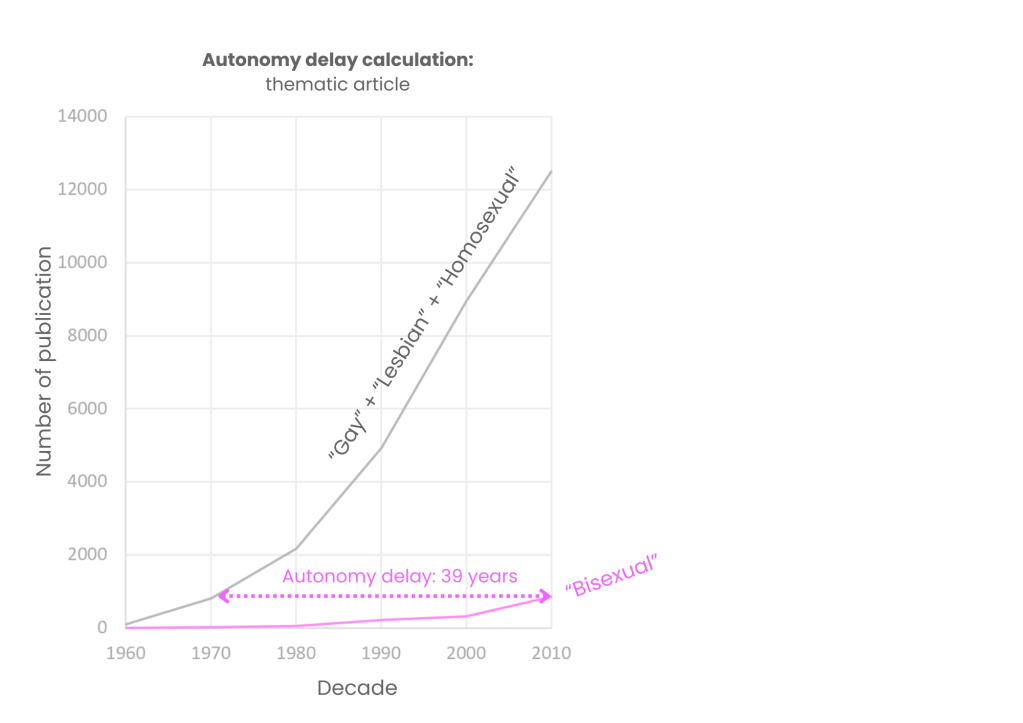

Despite this progress, the number of studies focusing exclusively on bisexual individuals remains marginal compared to research dedicated solely to gay men or lesbians. A historical analysis of published literature since the 1960s shows a consistent preference for gay and lesbian subjects. While the inclusion of bisexuality in academic research is increasing, bisexual people remain severely under-studied, despite growing awareness of their specific experiences and vulnerabilities (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Publications containing the keywords “gay,” “lesbian,” and “bisexual” by decade, from 1960–1969 to 2010–2019, compared to articles whose titles mention only one of these minority groups and not the others. Mentions of the term “bisexual” are further broken down by gender (light pink). The research methodology and raw data are detailed in Appendix 1.

Inclusion of Bisexual People from the 1980s

The number of scientific articles on the LGBT community began to rise significantly in the 1980s. During this period, we start to see the publication of studies that include bisexual people. However, bisexuals were not truly regarded as a group distinct from homosexuals; rather, they were treated as a subcategory within homosexuality. Researchers did not consider that bisexual individuals might face a specific form of discrimination, namely, biphobia.

For example, when searching for studies on depression among bisexual people between 1980 and 1995, two articles frequently emerge as highly cited: one by Proctor & Groze (1994) and another by D’Augelli & Hershberger (1993). In these studies, the term “bisexual” appears only in grouped phrases like “gay, lesbian, and bisexual.” The data is presented in aggregate form, with no distinctions made between gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals.

This model of inclusion without autonomy reveals a lack of awareness of bisexual people’s actual experiences. Specifically regarding depression, we now know that bisexual individuals suffer from depression at higher rates than both gay and lesbian populations (Ross et al., 2018). But to uncover this fact, researchers had to disaggregate bisexual people from other groups, something rarely done in studies from the 1980s and 1990s. Including bisexual individuals without distinguishing them from gays and lesbians reflects the mistaken belief that bisexuals experience only homophobia, not biphobia.

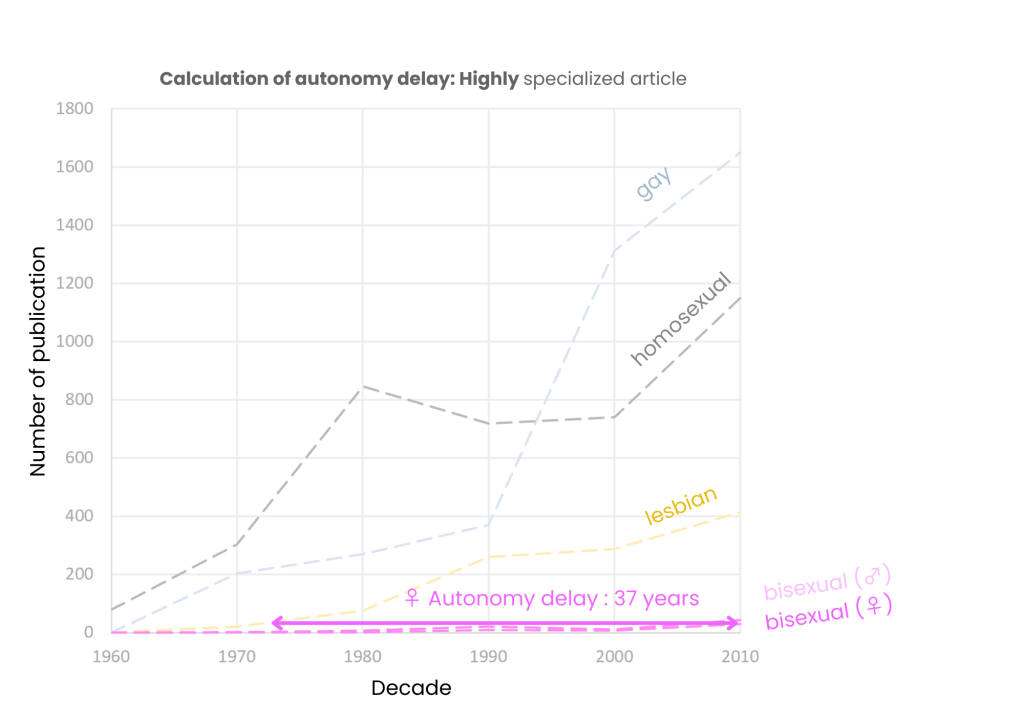

Years later, under pressure from bisexual activists, studies finally began to emerge in which bisexual people were examined as a distinct population from gays and lesbians. In these combined studies, statistics were presented separately for each group. While this development marked a crucial and long-overdue step forward, bisexual-specific research still lags far behind research focused on gay men and lesbians. If sexism can partly explain why lesbians are studied less than gay men, it does not account for the fact that bisexual men are studied less than gay men, or that bisexual women are studied less than lesbians (see Figure 1).

Figure 2: Highly Specialized Studies on Bisexuality from 1960–1969 to 2010–2019, Compared to Highly Specialized Studies on Gay Men, Homosexuals, and Lesbians. Highly specialized studies are defined as those that include the keyword in the title while excluding references to other sexual minorities in both the title and the body of the text. The research methodology and raw data are detailed in Appendix 1.

This underrepresentation is even more striking in highly specialized studies. As shown in Figure 2, between 2010 and 2019, there were more than 1,600 academic articles focused exclusively on gay men, with no mention of lesbians or bisexual people. In contrast, during the same period, there were approximately 400 specialized studies on lesbians and fewer than 30 on bisexual individuals.

The Compilation and Communication of Scientific Data: A Scientific and Activist Endeavor

The researchers and activists who have contributed to the quantification and dissemination of data on the effects of biphobia are numerous. However, the names remembered as influential in this field are often those of people who compile, summarize, or popularize the data. Unfortunately, there is far less symbolic recognition for work based on a single statistical study on biphobia. Among the major efforts in data communication and popularization, one can highlight the work of Julia Shaw (2022), whose book is the best-selling and most widely translated on the subject.

In France, the 2022 Biphobia and Panphobia Survey Report (Rapport d’enquête biphobie panphobie 2022), published by Act Up-Paris, Bi’Cause, MAG Jeunes LGBTQI+, and SOS homophobie, serves as a key national reference (Dilcrah 2022). On social media, both myself (Resa, 2021–2024) and Precarité Inclusive (2022–2023) have contributed to the popularization of quantitative scientific research on biphobia, reaching a certain level of visibility. In Belgium, the study conducted by Irène Zeiliger (2023) for the organization Garance is also widely recognized.

On the academic side, a number of review studies have focused on the heightened vulnerability of bisexual people in various areas, including: intimate partner violence (Bermea et al., 2018; Turell et al., 2018), suicide risk (Pompili et al., 2014; Salway et al., 2019), poverty (Ross et al., 2016), health outcomes (Feinstein & Dyar, 2017; Caseres et al., 2017), tobacco use (Shokoohi et al., 2021), addiction (Shultz et al., 2022), and premature mortality (McKetta et al., 2024), to name just a few of the most significant findings. All of these studies have helped demonstrate that bisexual individuals are more vulnerable than heterosexual, gay, or lesbian individuals.

However, this growing body of data still does not fully explain why or how biphobia is constructed. To address that question, another type of statistical research is needed, one that examines predictive factors and moderating effects.

A Preliminary Scientific Response: The Minority Stress Theory

Analyzing statistics can help identify what differentiates bisexual individuals who are doing relatively well from those who are more likely to experience suicidal ideation, poverty, or violence, for instance. While this type of analysis cannot definitively validate any one theory about the causes of biphobia, these predictive factors can nonetheless offer valuable insight.

At present, the dominant scientific consensus points to one factor that has consistently shown strong predictive power for the outcomes of bisexual individuals, and LGBT people more broadly: this factor is known as minority stress.

Minority stress refers to the chronic, everyday stress experienced by LGBT individuals due to their marginalized status. It comes on top of the general stress everyone faces. This specific stress is driven both by experiences of discrimination and by one’s own internalized perception of their sexual orientation or gender identity. Minority stress has been demonstrated as a predictive factor in a range of negative outcomes among LGBT populations, including cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline, mental health problems, and nicotine addiction (Li et al., 2024; Correro et al., 2020; Hoy-Ellis, 2023). Minority stress is also a key contributor to intimate partner violence experienced by bisexual women, among other issues (Bermea et al., 2018).

Yet a central question remains: Why do bisexual people experience higher levels of minority stress than gay men and lesbians? Here, the discussion re-enters the realm of theory and speculation. For many researchers, the explanation lies in the idea of double discrimination, that bisexual people face stigma from both broader society and from within LGBT communities themselves (ibid.).

I do not fully agree with any of these prevailing theories, neither Ochs’s view of biphobia as the product of accidental cultural bias within binary systems, nor Yoshino’s theory that it results from a social need to maintain binary classifications and monogamy, nor Eisner’s framework of monosexual privilege, nor even the theory of intensified minority stress due to compounded homophobia and biphobia. I do not believe these theories are wrong, but I do believe they fail to identify the original cause of biphobia.

In my view, these frameworks explain mechanisms that perpetuate biphobia, but not what created it in the first place. To understand the architecture of biphobia, we need a new theoretical framework, one that accounts for the complexity of bisexuality and its dimensions.

Part 2 – Toward a New Theoretical Framework for the Origin of Biphobia

To understand biphobia, one must first understand the fate of dual nationals in times of war. Like dual nationals, bi and pan individuals occupy an ambiguous position that, in moments of conflict, evokes mistrust and rejection. The “sin” of duality for bisexual people is only a sin because there is conflict. In times of peace, duality and fluidity pose no issue. This aversion to bisexual duality is the second cause of biphobia, but not the first. The primary condition for the emergence of biphobia is the attack of heterosexuality upon homosexuality. But first, let us examine the dynamics experienced by individuals who hold the nationality of both the aggressor and the attacked in times of armed conflict.

The Case of Dual Nationals in Wartime

Binational identity, often celebrated in peacetime for its diplomatic and cultural value, becomes a liability in times of war. These populations find themselves at the center of immense tensions, often perceived as potential traitors by both sides. In France, following the 2015 terrorist attacks, proposals were made to strip French citizenship from dual nationals convicted of terrorism, provoking national debates on loyalty and the stigmatization of dual nationals (Geisser, 2016). The oppression of dual nationals typically manifests in three major dynamics: suspicion of betrayal, forced assimilation, and exploitation.

Suspicion of betrayal can take the form of surveillance and control of binational and biethnic populations. After the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, approximately 120,000 people of Japanese descent living in the United States, many of them American citizens, were interned in camps on suspicion of loyalty to Japan (Robinson, 2012). When they are not surveilled or imprisoned, these populations are harassed or driven into exile, particularly when they live in the less powerful nation in a conflict. For example, after World War II, the Sudeten Germans, many of whom held both Czechoslovak and German nationalities, were perceived as traitors within Czechoslovakia. This community, present in Bohemia and Moravia since the 12th century, was subjected to brutal persecution beginning in 1945, including forced displacements under inhumane conditions. Between 1945 and 1947, three million people were expelled; tens of thousands, mostly women, children, and the elderly, died in the process (Brouland, 2017).

Dual nationals may also be viewed as infiltrators or privileged insiders within the oppressed nation. In the 1970s in Vietnam, the Hoa, an ethnically Chinese and Vietnamese minority, were subjected to defamatory campaigns and mass expropriations by the Vietnamese government due to rising tensions with China. China’s attempts to defend the Hoa only exacerbated suspicion. The persecution escalated to such a degree that it triggered a massive exodus. Fleeing in dangerous conditions aboard makeshift boats, these refugees became known as the “boat people” (in English in French culture) (Benoit, 2019). Whether they reside in the powerful aggressor state or in the attacked nation, dual nationals are systematically oppressed during and after wartime.

In addition to suspicion, dual nationals are often subjected to forced assimilation strategies intended to erase their dual cultural identity, for instance, by banning one of their native languages or reducing their cultural heritage to folkloric tokenism. In Canada, up until the late 20th century, Indigenous children were often placed in residential schools where their native languages were banned. These practices of assimilation and abuse have since been nationally acknowledged (Bousquet, 2012). The ethnic group known as the Métis, descended from both Indigenous and Canadian settler lineages, was especially affected. Many Métis children raised in Indigenous cultural environments were sent to residential schools, where they were marginalized both by school authorities and by Indigenous peers. They were also excluded from the first rounds of government compensation for residential school survivors (Logan, 2020).

As Belzile (2021) reported for Radio Canada, several high-profile cases of cultural appropriation involved individuals falsely claiming Métis identity to gain cultural or institutional capital, as shamans, artists, or academics. These revelations, alongside a growing number of people claiming Métis identity, have led to a climate of intensified suspicion. The Métis thus face a dual form of oppression: on one hand, cultural appropriation, and on the other, suspicion that their identity is fraudulent.

The oppression of homosexuality by heterosexuality is an ideological war, not a territorial or colonial one. Biphobia is not comparable in magnitude to the violence experienced by dual nationals in armed conflicts or colonization. Yet understanding the complexity of these situations, and particularly the role of oppression in shaping the conditions of binational targeting, helps us understand the structure of biphobia.

The Symbolic Dual Nationals of Lesbos

Today, the heterosexual superpower oppresses the insular and isolated lesbian “island.” Much like dual nationals during wartime, bisexual women face oppression and suspicion, regardless of their current relationship status. On the side of Heteroland, they are discouraged from building a life with women and grow up without positive representations of same-gender love. They are shamed and discriminated against if they live a lesbian life, or are merely suspected of doing so. Evidence of bisexuality being documented and pathologized still appears in psychiatric records, where a patient’s bisexuality is sometimes noted and associated with mental instability (Ross & Costa, 2021).

Bisexual women are exoticized and pressured to provide threesomes. They are staged and hypersexualized in narratives tailored to heterosexual erotica, particularly in mainstream pornography. When PornHub, one of the largest adult content platforms, declared “lesbian” as its most popular keyword, researchers found that many of those videos actually depicted bisexual scenes rather than exclusively lesbian ones (Bowling & Fritz, 2021). These researchers also identified that videos portraying exclusively lesbian scenes were more often targeted toward female audiences than bisexual scenes. Lesbian scenes were less likely to depict aggression and more likely to center on female pleasure and orgasm. In contrast, bisexual scenes featured fewer depictions of female orgasm and showed more frequent combinations of anal sex, fellatio, and vaginal penetration than either heterosexual or lesbian content. After analyzing over 1,000 pornographic films, the researchers concluded:

“We found significant differences in sexual behaviors and aggression among Heterosexual, Bisexual, and Lesbian categories of pornography. Bisexual scenes had higher frequencies of aggression and behaviors [e.g., fellatio, anal sex, vaginal penetration], except for depictions of female orgasms, than heterosexual and lesbian categories.” (Bowling & Fritz, 2021)

We can thus observe all the classic dynamics employed by powerful nations in the oppression of dual nationals during wartime: control, forced assimilation, exoticization, and cultural exploitation for the benefit of the oppressor.

Studies also show that the more homophobic a heterosexual person is, the more negative their attitude toward bisexual people, and the more likely they are to endorse harmful stereotypes. This aversion is even stronger than the one directed toward gay men or lesbians (Eliason, 1997; Nagoshi et al., 2023). This finding supports the homophobic origins of biphobia and helps distinguish it as a separate yet related form of oppression.

On the lesbian side, bisexual women are not always welcomed as sisters. Biphobia has been consistently documented within gay and lesbian communities (Friedman et al., 2014; Hertlein et al., 2016). Accusations of betrayal or privilege are common (Armstrong, 2014; Nelson, 2024). One emblematic case is that of Lani Ka’ahumanu in the United States, a bisexual woman who was excluded from lesbian spaces despite her long-standing activism (Rose, 2022). These instances mirror the suspicion directed at dual nationals even within oppressed nations.

I argue that this condition is not the result of a mere aversion to duality, but of the oppression of homosexuality by heterosexuality. Just as in wartime, only dual nationals belonging to both conflicting sides are targeted, not all dual nationals. For example, Irish-American dual citizens were not interned after the Pearl Harbor attack; Japanese Americans were. Likewise, in the LGBT community, “dual citizens” who are not suspected of having ties to heterosexuality are treated differently. For instance, asexual and homoromantic women, those who are not sexually attracted to anyone but are romantically attracted to women, are often accepted as lesbians. Within LGBT jargon, they are referred to as “Bambi lesbians” (Maskell, 2024), reflecting their perceived 100% lesbian status, despite lacking sexual attraction to women.

In contrast, bisexual women are not perceived as fully lesbian precisely because they are also attracted to men. In a world where heterosexuality had never violently oppressed lesbians, biphobia might never have emerged, neither in broader society nor within the lesbian community itself.

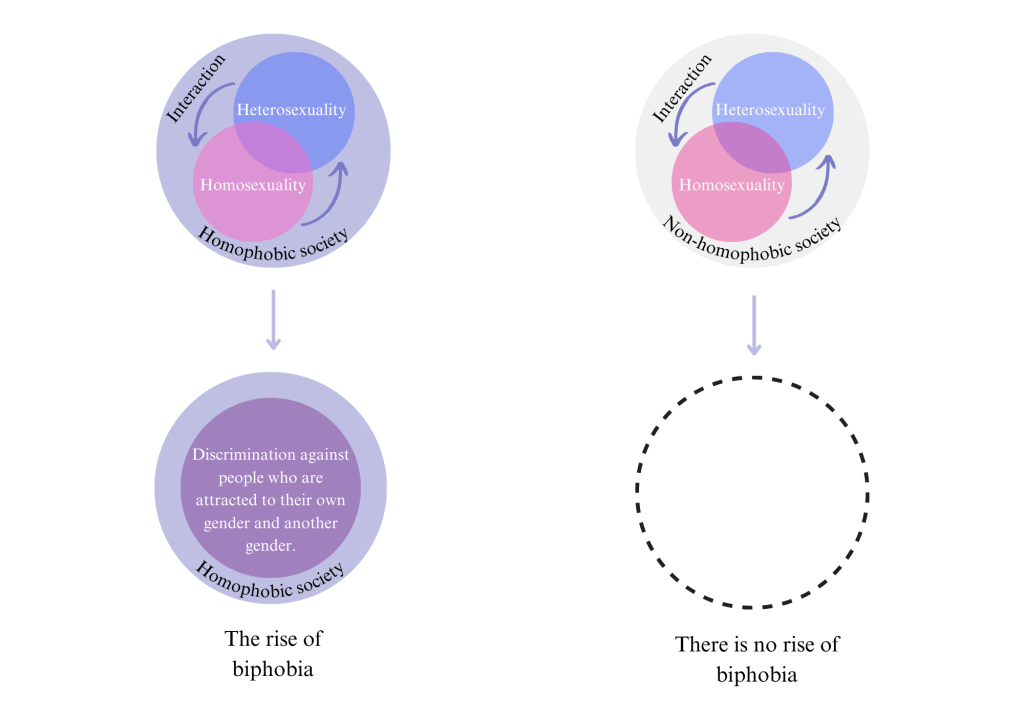

Figure 3 : Diagram of the Formation of Biphobia – A Homophobic Society as a Prerequisite for Biphobia

In conclusion, I am convinced that biphobia originates first and foremost from homophobia, and only secondarily from the bisexual interaction of heterosexuality and homosexuality. Its structure mirrors the architecture of wartime oppression against dual nationals (see Figure 3).

In political and theoretical discourse on biphobia, the idea that biphobia is driven by a need to uphold patriarchal order is widespread. This view is central to the theories of both Yoshino and Eisner. I do not believe this hypothesis is accurate. I argue that a patriarchal society that is not homophobic does not give rise to biphobia. I will illustrate this point by examining the situation in Tahiti, in French Polynesia.

Case Study: The Tahitian Context

Tahiti, despite its idealized image, experiences high levels of domestic and gender-based violence (Cerf, 2007). Even prior to Western colonization, the culture was marked by structurally sexist norms. Women were considered religiously impure, and the island operated under a patriarchal hierarchy that penalized women from lower classes. In the more inhospitable island regions, women were enslaved, and infanticide of female babies was practiced (Langevin-Duval, 1979).

And yet, Tahitian society has long accepted as natural same-gender relationships, masculine women, and feminine men. I was first introduced to this reality through conversations with a Tahitian woman I will refer to as Tatiana. In informal discussions, I learned that three members of her family were part of sexual or gender minorities, without it being a source of conflict. In her words, she had a “feminine uncle, raerae”, her husband’s mother lived with a woman, and her cousin had had both male and female partners throughout her life.

When I asked whether people made fun of her effeminate uncle, whom she often mentioned, she said that French people and foreigners did, but only because “they don’t understand the raerae.” She added, “Here in Tahiti, it’s natural. It’s always been like this.” She struggled to explain what the raerae were, describing their graceful gestures, feminine clothing, and mannerisms. When I asked if raerae were gay men, she said no, her uncle was married to a woman. I also asked about masculine women, lesbians, and transmasculine individuals. She brushed the question aside, saying: “It’s the same thing. They’re raerae.”

This exchange was my first introduction to the topic. I had to do further research to better understand who the raerae were and how homophobia manifested, or didn’t, within Tahitian society.

Tahiti is an example of a sexist but not culturally homophobic society. It is often described as a “paradise for LGBT tourists.” A business article by Masters (2023), aimed at queer travelers and promoters, notes that there are no gay bars in Tahiti because all bars welcome all kinds of people to celebrate together. Homophobia and transphobia in Tahiti are largely imported from Europe, particularly via Christianization and French institutions such as schools and police. This was confirmed by the local LGBT association Cousin-Cousines in interviews with the press (Martinez, 2023; MG, 2023).

To better understand the situation, I spoke with an activist from the association. She explained that LGBT teens are mostly kicked out of their homes for religious reasons, particularly in Christian families, and that the more religious the environment, the more abuse occurs. Westernization has increased the difficulties sexual minorities face within their families and heightened experiences of violence. Still, Campet (2009) observes significant tolerance in the Tahitian communities she studied, especially toward local sexual and gender minorities.

There is, furthermore, a clear distinction between Western conceptualizations of homosexuality and the pre-colonial social structures of the islands. The terms raerae and mahu describe different types of gender and sexual minorities, with raerae being the more recent term. This difference became politically contentious during the debates around France’s same-sex marriage legislation. At the time, a Polynesian deputy opposing the law declared: “In French Polynesia, we don’t have the same kind of homosexuals as in mainland France. We have our raerae, we have our mahu, but they are not the same homosexuals.”

The situation is far from ideal for LGBT people, but culturally, it is clear that male dominance over women has not translated into a specifically Tahitian form of homophobia or transphobia. So what about biphobia in this context?

According to the theories of Yoshino and Eisner, biphobia should arise in order to reinforce patriarchal norms. And yet, in Tahiti, this is not the case.

Can a Patriarchal but Non-Homophobic Society Be Biphobic?

Tahiti has more deeply rooted sexist norms than many Western societies, but it is also lesshomophobic. If my theory is correct, then biphobia should be more present in the most Westernized, and thus more homophobic, sectors of Tahitian society. Conversely, if the theories of Yoshino and Eisner are accurate, biphobia should be most visible in the least Westernized, and therefore most patriarchal, sectors of society.

Evaluating biphobia or the place of bisexuality in Tahiti is complicated by the fact that bisexuality is a Western concept. Thus, speaking about biphobia in the Tahitian context is not straightforward. However, what we can examine is the place of sexual and gender fluidity within Tahitian society.

The mahu, individuals assigned male at birth who take on female roles and have sexual relationships with men, are an example of socially integrated gender fluidity. A mahu may later stop identifying as such, marry a woman, and have children (Campet, 2002). Temporal fluidity is therefore tolerated within this social category. A similar flexibility exists for women. Tahitian anthropologist Natea Montillier Tetuanui describes what she refers to as female raerae in these terms:

“A female raerae behaves and sees herself almost as a man, dresses like a man, but still uses the women’s restroom. She may adopt children from within the family. At home, she participates in both women’s and men’s activities, such as cooking, woodworking, and fishing. She chooses her profession based on her skills, whether it is a traditionally male or female role. A young woman might try dating a man, then go on to settle down with a woman. One of the two women tends to remain more feminine.” (Montillier Tetuanui, 2013)

These raerae women can transition from heterosexual relationships to long-term same-gender relationships without losing their social identity. Moreover, they can freely move between gender-coded activities without being stripped of their raerae status. For many Western observers, the raerae category is mistakenly conflated with sexual orientation, but it is more accurately a gender identity than a label for sexual preference. As Campet (2002) explains, raerae assigned male at birth may engage in same-gender relationships, but that does not make them mahu. Here again, fluidity and duality are accepted within the very category of raerae.

However, this nuance is often erased in Western anthropological literature. Several academic sources portray the raerae exclusively as men who have sex with men. For instance, Stip (2015) defines raerae as a category assigned male at birth and discusses only their male lovers. Lacombe (2008) goes so far as to deny that raerae may have sex with anyone other than men, stating:

“While raerae do not consider themselves homosexuals, the majority, if not the entirety, of them maintain sexual relationships with men, whether those men are aware of their singular condition or not.”

It is also remarkably difficult to find anthropological sources discussing raerae assigned female at birth. Aside from my conversation with Tatiana and the work of Montillier Tetuanui, I found no sources addressing raerae as women.

By presenting raerae exclusively as homosexual men, Western anthropologists project a binary framework that erases large segments of raerae identity. All available evidence suggests not only that raerae are not perceived as “homosexuals” (probably because those assigned male at birth are not perceived as men), but also that their sexuality is not exclusively directed toward men. If there is a binary at play, it exists in the eyes of the Western ethnographer. Thus, in its traditional, less Westernized forms, Tahitian culture embraces relational and gender fluidity, for both individuals assigned male and female at birth.

In my personal interactions, I noted that Tatiana, the Tahitian woman I spoke with, mentioned her cousin’s bisexuality without judgment. She also responded very positively when I came out as bisexual. I had never experienced such a smooth and easy coming out. When I mentioned my divorce from my ex-husband and my breakup with my ex-girlfriend, she asked no intrusive questions, showed no surprise, and simply expressed concern for the emotional toll of my most recent breakup, the one with my female partner. I must stress how unique this experience was. Never in my life had I mentioned my bisexuality without it triggering either hostility, awkward questions, discomfort, or, at best, a performative show of support.

For Tatiana, my bisexuality both existed and didn’t exist. She registered the information, but it required no special response. She simply hoped I would heal from my heartbreak and find love again. Her attitude toward me didn’t change. She had liked me before knowing I had been married to a man for fifteen years and had recently been in a relationship with a woman for a year and a half, and she continued to treat me with the same warmth and friendliness afterward.

Tatiana had the following profile: a woman without higher education, owner of her inherited home in Tahiti, employed in the tourism industry. She wore traditional tattoos, a flower in her hair daily, spoke fluent Tahitian, had danced professionally in traditional settings, and had allowed her underage son to get a tattoo of a turtle and flower before the age of fifteen, practices very different from Western norms. She used TikTok, had stopped attending church for several years, and spoke fluent French. She had temporarily moved to mainland France with her family to work and save money. She had also experienced serious domestic violence in a prior relationship. Tatiana straddled both Western and traditional Tahitian cultural spheres. Her attitude toward my bisexuality aligned clearly with the more traditional, less Westernized aspects of her background.

Altogether, there is a body of evidence suggesting low levels of biphobia and strong acceptance of sexual and gender fluidity in highly Tahitian and minimally Christianized cultural contexts in Tahiti.

What about the more Westernized and homophobic sectors of Tahitian society?

Biphobia in Contexts Affected by Homophobia

To better understand the situation, I spoke with a South American activist who had settled in Polynesia, we will call her Ofelia. She had grown up in a country marked by terrorism and military coups and described a clandestine LGBT environment, including police raids on bars frequented by queer people. When leftist activists began to disappear, she and her friends fled, and she eventually resettled in Polynesia.

Ofelia identifies as pansexual, was married to a man, has children, and has been active in LGBT rights advocacy in Tahiti. Like the activists from the association Cousin-Cousine, she described extreme violence faced by gay, bi, and lesbian adolescents in the most religious Christian families, and explicitly identified Christian churches in Tahiti as the primary source of homophobia and related social problems.

She described the activist landscape as follows: in Tahiti, there is only one LGBT association, with a well-followed Facebook page but few dues-paying members. Of those, only a small number are active participants in meetings or events, which makes it difficult to speak for the entire community. There are also informal groups on Facebook: dating groups, mostly for men, and two women’s groups, one public, intended for women who love women, whether residents or travelers; and another, a private circle of mostly lesbian friends who organize activities together.

The broader LGBT community includes residents of European descent, demis (people of mixed European and Polynesian heritage), and a few Polynesians, often those from more Westernized backgrounds. People more rooted in traditional Tahitian culture generally avoid LGBT associations, preferring to participate in cultural organizations. Interestingly, many local artists are gay or bisexual.

Regarding bisexuals, they are, in principle, fully included in LGBT spaces and associations. However, a certain suspicion remains. Many believe that a bi person, whether in a heterosexual or homosexual relationship, will eventually seek out the other gender to achieve some notion of « completion. » Ofelia, who identifies as pansexual, does not share this biphobic view. She also noted a double standard in LGBT spaces: those with a heterosexual past but currently in same-sex relationships are well accepted, whereas those currently in heterosexual relationships but with a same-sex past are often less welcomed.

She also offered insights into how Tahitians perceive bisexuality. According to her, bisexuality is not really seen as a concept in Tahiti. Instead, people observe behaviors: men occasionally engaging with effeminate partners; women experimenting with other women; individuals attracted to both genders but not openly labeling it. Generally, she explained, bisexuality is less understood than trans identity, which has clearer cultural references and is better integrated due to its alignment with traditional gender codes.

Her account supports the idea that biphobia is present within the LGBT community, a space that is itself highly Westernized and shaped by Christian homophobia. Rejection of bisexuality within Christian communities mirrors the rejection of homosexuality.

If the maintenance of patriarchy were the root cause of biphobia, then Tahitian culture would not tolerate the kind of relational fluidity it clearly does. Nor is it about a cultural need for rigid categorization: Tahitian society has effectively categorized fluidity through concepts like raerae, without societal disruption, and even allows for movement in and out of the more binary mahu category. In contrast, the LGBT community, made up largely of survivors of Christian violence and shaped by Western norms, displays a familiar pattern of biphobia, exactly as my theory predicted.

Understanding homophobia as the foundational condition for biphobia not only better predicts where biphobia will arise, but also offers clearer insight into the internal dynamics of the bisexual community. For example, it helps us understand why bisexual men are often treated like gay men, while bisexual women are treated like heterosexual women…

The Homophobic Origins of Biphobia: The Case of Invisibility

Biphobia targeting women and biphobia targeting men share similarities, but they are not entirely identical. In Eisner’s framework, patriarchy and sexism are the primary forces behind biphobia, shaping the distinct ways bisexual men and women are treated. She develops this argument by pointing to what she calls phallocentric adoration as the root of the differing forms of invisibility experienced by bi men and bi women. She writes:

“(…) bisexual women are actually straight, while bisexual men are actually gay. The idea presented here is that of the immaculate phallus, suggesting that phallic adoration is the one true thing uniting all bisexual people. It projects society’s own phallocentrism onto the idea of bisexuality. This permits us to critically reflect this phallocentrism back into society, exposing the underlying system of sexism and misogyny as we do so.” (Eisner, 2013)

Eisner’s thinking is deeply influenced by the text “Phallocentrism and Bisexual Invisibility” by Michael Rosario, which she cites in her book. Rosario writes:

“It is very easy to receive the gay membership card if you’re a boy. You touch a cock, and that’s it. You’re gay. Forever. … To be honest, I didn’t even have to touch a cock to get it. Before I touched one, all I had to do was to say, hey, I wouldn’t mind touching one. … From that very moment nobody ever disputed that I could be gay[,] [though] [i]t’s certainly disputed that I’m bisexual…. I could never be heterosexual. Not that I’d want to, but even if I wanted to, I couldn’t. I’ve hooked up with boys and that disqualifies me. … If I request the heterosexual membership card I get the application returned with the stamp: DENIED. REASON: COCKSUCKER. … And I constantly have to … request the bisexual membership card by special delivery, only to have my application returned to me …” (Eisner, 2013)

Thus, Eisner sees the invisibility of bisexual men as a function of sexist and phallocentric mechanisms. According to her, the “contaminating” effect of male homosexuality stems from society’s symbolic obsession with the penis. But it is not adoration of the penis that “contaminates.” It is not because fellatio is valued that gay and bisexual men are labeled as gay. On the contrary, being a “cock-sucker” is heavily stigmatized, and that stigma has a name: homophobia.

Failing to understand the architecture of biphobia leads to frameworks that appear logical but overlook lived reality. In this case, for example, ignoring the evident homophobia that bisexual and gay men experience in relation to this idea of contamination distorts the analysis.

My critique of Yoshino and Eisner’s theories is that they portray sexism as the parent of biphobia, when it is, at best, its grandparent. The true parent of biphobia is the stigma surrounding homosexuality. I do not believe that bi men are perceived as gay, and bi women as straight, because society supposedly values only sex with men or worships the erect penis. The key difference in how bisexual men and women are treated lies in the homophobic foundation of biphobia.

Male homosexuality is perceived as contaminating in a way that lesbianism is not, because lesbophobia follows different logics than the oppression directed at gay men. For this reason, I will now take the opposite approach to Eisner: I will not focus solely on sexism, but instead examine the stigma against gay men, and then against lesbians, as the more accurate way to understand this divide.

Can homophobia better explain the differing treatment of bisexual men and women?

Homophobia

To better understand how male homosexuality is treated, let us look at the example of ancient Greece and Rome. These societies are often portrayed as politically bisexual systems, where being bi was considered the norm. However, in truth, free men and citizens were not permitted to be bisexual in the modern sense. Men of high social status were patriarchs who had the right to penetrate women, as well as slaves, male sex workers in Rome, and adolescent boys in Greece (Lear 2013; Verstraete 1980). Sexual relations between two adult men of equal social status were deeply frowned upon and heavily stigmatized (Worthen 2016). In these societies, sexuality and penetration were tools of domination.

I am not saying that every penetrative act is an act of domination. But it is an act of domination when it is used to assert power or humiliate the other person. It is domination when there is no consent. When it involves the uncompensated sexual service of one body for another. When it is mandatory or prioritized. When it consists of masturbating one’s own genitals inside another person. Pardon my French.

Penetration is not an act of domination when all the conditions of equality are met: when the penetrated person is equal in rights, value, and social consideration to the person penetrating; when there is active, enthusiastic consent; when both parties mutually exchange sexual services in a reciprocal and egalitarian way; when penetration is optional and secondary; and when it is done primarily for the pleasure of the person being penetrated.

Let’s note that if the pleasure of the person being penetrated were truly prioritized, straight men would use sex toys more often. Sex toys are known to bring significant pleasure with minimal effort. However, they provide neither social status nor erogenous stimulation for the penetrating partner, perhaps one reason why they are so underused in heterosexual encounters.

To be clear, penetration is not inherently dominating when it occurs:

- between equals,

- with consent,

- as an optional act,

- and when it is for the pleasure of the person penetrated.

Ultimately, even a trashy, balls-clapping doggy style session[1] can be totally egalitarian in traditional monogamous straight relationship, if and only if all of the following conditions are met, with the first being the most critical:

[1] You have no idea how much gets lost in the English translation. Since I know how much Americans love my native language, I should clarify that the original term was levrette claquée, not ‘balls-clapping doggy style.’ It means exactly the same thing, but it definitely sounds better in French. Yes, we have a word for that. And I think it’s beautiful. It’s pronounced luh-VRETT klah-KAY. You are welcome.

- He has signed a marriage contract that guarantees dignified post-divorce living conditions for her;

- She doesn’t have to sacrifice her career for his;

- He won’t leave her for someone younger;

- He tracks his contribution to household chores on a spreadsheet;

- He supports her mental health and provides stability;

- He is equally competent and committed to her pleasure as she is to his;

- He stands up for her against the minimization of her skills and intellect;

- He publicly challenges rape jokes and the degradation of female sexuality;

- She has expressed overflowing and continued enthusiasm for said levrette claquée;

- She has other options than that sexual act;

- And finally, the levrette claquée is open to both genders.

Too often, men who consider themselves « woke » focus on prostate play and female orgasm while continuing to ruin the mental and financial health of the women they take from behind. That is not what I call egalitarian doggy style.

I include this aside for readers who might be disturbed by the association I make between penetration and domination. If that association exists in society, it is entirely possible to redefine it in individual relationships. However, I am not speaking here of individual relationships, but of societal structures, and within both modern and ancient societies, penetration has indeed been used as a tool of dominance.

Thus, ancient Greece and Rome were not bisexual or even homosexual systems, but rather variants of modern heterosexual patriarchy. Sexual dominance was exercised over the “other gender”, meaning anyone who was not a high-status adult male. Dominant men were strictly forbidden from being passive or penetrated in their sexual practices.

Australian sociologist Raewyn Connell, who pioneered academic research on masculinities, defines hegemonic masculinity as the dominant model, and identifies subordinate, complicit, and marginalized masculinities as subjected to it. Men marginalized by race, class, or disability fall under what she calls marginalized masculinities. According to Connell, the dominant man exerts power over other men, and particularly over gay and bisexual men, whose identities are categorized under subordinate masculinities.

She describes homophobia as co-constructed with heterosexuality, stating:

“Heterosexual masculinity did not predate homophobia but was historically produced along with it.” (Connell, 1992)

According to Connell, heterosexual masculinity is built not only through the domination of women, but also through the exclusion of gay and bisexual men from the ranks of the dominant. Male homosexuality is thus stigmatized because it removes a man from his superior position and places him in a subordinate masculinity. Because penetration is symbolically charged in this system, gay men perceived as passive are particularly devalued. The virile, active gay man is less stigmatized than the femme, the sissy, or the bottom (Taywaditep, 2002; Wang, 2025). However, it is important not to assume that only passive gay men are discriminated against, male homosexuality as a whole remains subordinate to hegemonic masculinity.

As a result, homophobia directed at men is « contaminating ». But it is not the contact with a penis that contaminates, it is the contact with submission. The masculinity embodied by homosexuality is subordinate to that of the dominant heterosexual man, and that is what contaminates.

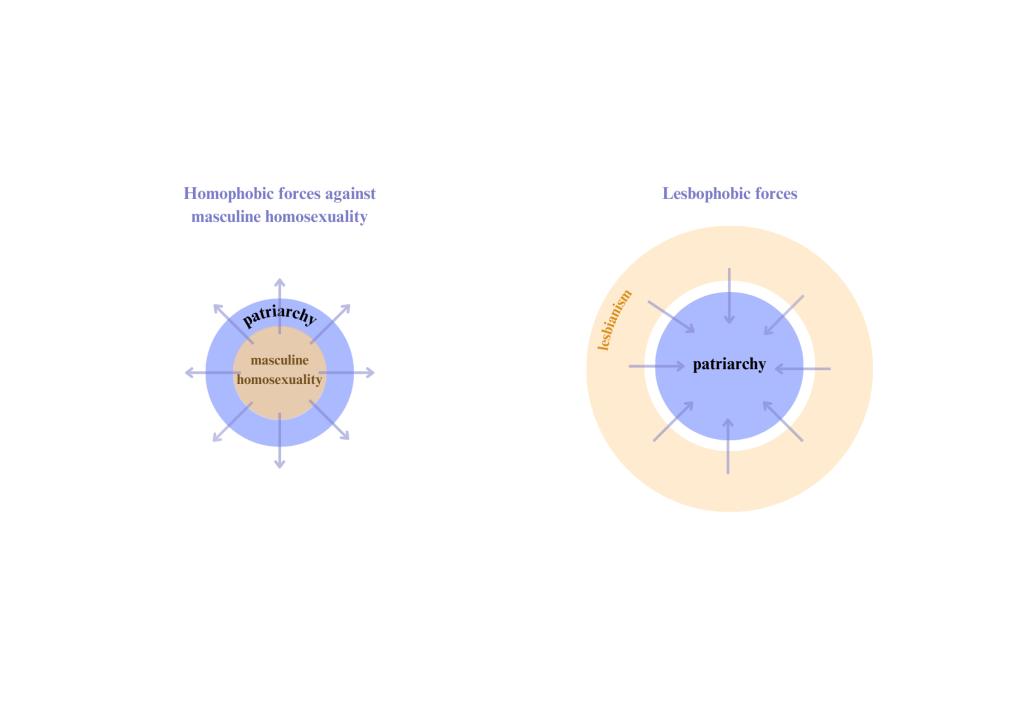

Thus, proximity to homosexuality for men, and to heterosexuality for women, defines their subordinated rank. A single contact that signals submission is enough to mark someone as subject to the authority of dominant men. This “contaminating submission” has profoundly shaped the difference between homophobia targeting gay men and lesbophobia.

Lesbians are perceived as escaping male domination. In patriarchy, they must be brought back into line, as they have rejected heterosexuality. Gay men, on the other hand, must be ostracized, as they have betrayed their rank. Lesbianism must be tamed; being gay merits exclusion.

From the perspective of systemic force:

- Homophobia targeting gay men is centrifugal (pushing from the center to the periphery);

- Homophobia targeting lesbians is centripetal (pulling from the margins toward the center).

(See Figure 4.)

Figure 4: Diagram of the Different Forces of Homophobia Depending on Whether They Target Male or Female Homosexuality.

The Difference Between Bi People on the Lesbian Spectrum and Bi People on the Gay Spectrum

The forms of biphobia experienced by women and men are not exactly the same, because gays and lesbians are not treated in the same way. The part of bisexuality perceived as deviant, homosexuality, is not subject to the same oppressive forces depending on whether it is expressed in men or women. This has shaped how biphobia has evolved on a broader scale: it mutates, adapts, and responds to its environment and to different normative pressures.

Bi women are perceived as straight, and bi men as gay, because both are understood in terms of their submission to hegemonic masculinity.

One might argue that, in the end, sexism is still the root force at play. My goal is not to deny the role that sexism plays in biphobia, only to emphasize that its role is secondary. When people claim that bisexual discrimination stems solely from patriarchy, they consistently erase the role of homophobia. This erasure is especially visible in Eisner’s argument on phallocentrism. When a bi man says, essentially, “I’m not considered bi because I sucked a dick,” Eisner fails to identify this as a clear manifestation of homophobia, instead theorizing around the idea of an “immaculate phallus.”

My aim is not at all to deny the theoretical contributions of those who came before me, but rather to bring homophobia back into the picture, to relegate marginal influences to the margins, and to formulate a clear and direct equation of biphobia, one that doesn’t rely on indirect forces alone.

According to Yoshino and Eisner, homophobia is itself derived from patriarchy, which implies that biphobia and homophobia are on the same structural level. In their framework, sexism is the primary oppression, while both homophobia and biphobia are secondary oppressions. Perhaps for some, this hierarchy elevates bisexual discrimination to the same « evolutionary tier » as homophobia against gays and lesbians, making it feel more serious or legitimate.

But I do not believe these oppressions are structurally identical. However, in arguing that biphobia stems from homophobia, I am not claiming it is less serious, or that bi people are somehow subordinate to homosexual people. What I am claiming is that the architecture of biphobia is more complex.

That said, I am not equating biphobia with homophobia. Just as I am not the same person as my parents, biphobia is not the same oppression as homophobia. I also do not believe that oppressions should be ranked by their degree of complexity. My focus is simply to theorize biphobia, in the hope that we can fight the violence bisexual people face more effectively if we understand it better.

What Are the Consequences of Failing to Recognize the Homophobic Roots of Biphobia?

Misunderstanding the architecture of bi oppression leads to discourse and actions that are ineffective. The further a narrative strays from reality to uphold a theory that doesn’t hold up, the less it can offer concrete applications for bisexual people.

Let’s imagine, for example, a bisexual advocacy group trying to launch a public awareness campaign focused on the experiences of bisexual men. They explore two proposals. The first is based on Eisner’s theory, which suggests that bisexual men are oppressed through phallocentrism and society’s worship of the erect penis. The second campaign is based on an analysis that identifies homophobia as the root of biphobia, and emphasizes the distinction between the two.

So the organization must choose between:

Option 1 – Fighting phallocentrism:

- “Stop worshipping dicks.”

Option 2 – Addressing homophobia and biphobia separately:

- “Men who go down on other men? That’s okay.”

- “Some men are into both guys and girls. That’s called bisexuality, and that’s okay too.”

Option 2 may be less exciting from a theoretical standpoint, but it’s more anchored in lived experience. It’s also more complex, because it involves two layers of messaging, but it better reflects the reality of biphobia. I believe it is crucial that we recognize when we’ve made a misstep, and that we remain capable of evolving in order to better serve the bi and pan communities.

From this point on, I will primarily focus on biphobia directed at women and people perceived as such. I will concentrate specifically on the lesbian spectrum of bisexuality. As a result, I encourage bi and pan men to take ownership of the concepts that concern them, and to develop a masculine bisexual theory that addresses bisexuality on the gay spectrum.

I’m fully aware that the bisexual community today is primarily organized and theorized by women, and that bi men are still in the minority for now. I also acknowledge that there are bi and pan individuals who move fluidly between gay and lesbian communities, who transition, and/or who are non-binary, and whose relationship to gender and sexuality is more complex. I invite those individuals, too, to contribute to a bisexual theoretical framework that reflects the broad diversity of bi and pan experience.

To return to the central thesis: Biphobia was born from homophobia. But these are distinct forms of oppression. So, what exactly is the difference between them, and how do they impact bisexual women?

Part 3 – Biphobia and Lesbophobia: Two Distinct Forms of Oppression

In my activism, I have often heard the argument that bisexual women may experience homophobia, but only when they are in a relationship with another woman, and that biphobia simply doesn’t exist. This belief is so deeply rooted that one of the key slogans of the French association Bi’Cause, chanted during the 2022 Bi Visibility March in Paris, was:

“Bisexuality exists, and so does biphobia.”

I can still hear the voice of Vi-vi, a member of the oldest bi and pan association in France, repeating that phrase over and over through a megaphone.

“La bisexualité existe, la biphobie aussi.”

The belief that biphobia doesn’t exist remains a serious issue to this day.

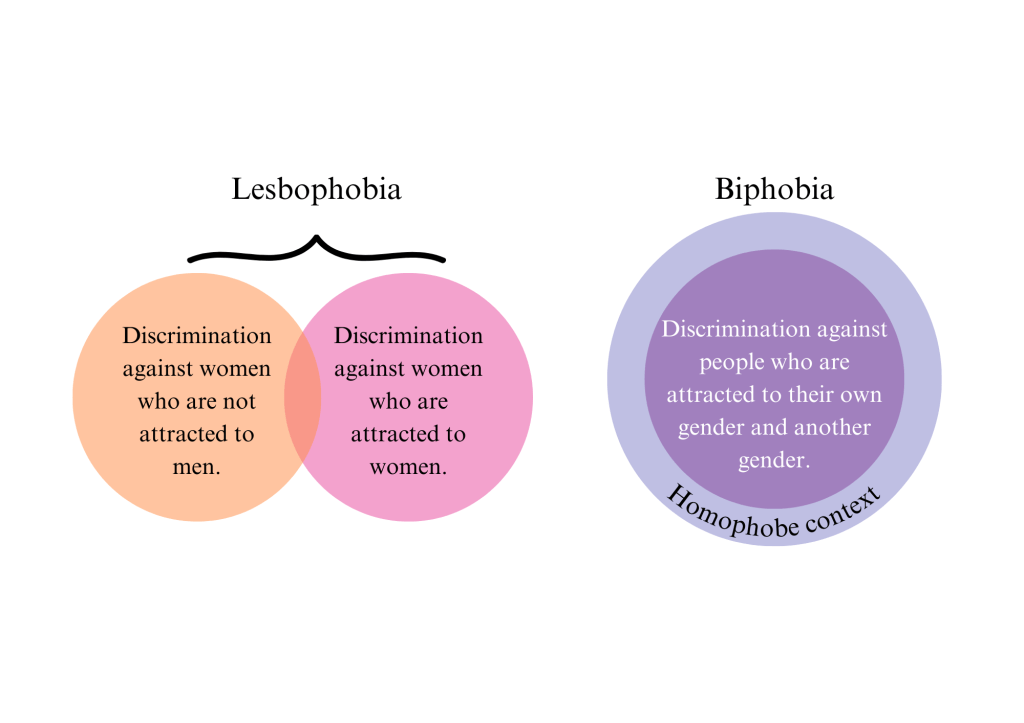

Yet I cannot speak about biphobia without first addressing the lesbophobia that bisexual women face. Because more often than not, the same people who deny the existence of biphobia also deny the reality of homophobia experienced by bi women.

Denial of the Homophobia Experienced by Bi Women in Heterosexual Relationships

There is a dominant narrative that denies the existence of lesbophobic oppression experienced by bisexual women who are single or in heterosexual relationships. This discourse is also present within the bisexual community itself, and many bisexual people actively uphold it. This belief is not necessarily ill-intentioned, it can be expressed in subtle or even caring ways.

For example, a former lesbian partner once told me that she often felt guilty for exposing me to lesbophobia simply by loving me. I found this statement particularly striking. She was not my first female partner, for one thing. But more importantly, I was puzzled by the power dynamic implied in her words. In her view, it was her love that brought me into the realm of lesbophobic oppression. I doubt she would have said the same about my love exposing her to oppression. And yet, I was the one who had made the first move in our relationship.

She still felt responsible for the lesbophobia I experienced, because she loved me. This confession revealed a deeper belief: that bi women are not exposed to lesbophobia outside of their relationships with women. The first way this homophobia is denied, then, is by reducing it to something that only occurs within lesbian couples, and not outside of them.

And yet, a bisexual woman was once a little girl, raised on stories about princes charming princesses, but never princesses charming each other. Like lesbians, bisexual girls grow up in a society that erases the possibility that they might one day love women. When they become teenagers and adults, their same-gender desire is mocked, punished, and degraded.

Loving women doesn’t just have consequences when it’s mutual. Growing up in a world that hates the idea of women loving women is profoundly violent for those affected by it.

So let me be clear: bisexual women experience the effects of lesbophobia long before they know they are attracted to women, and long before they ever enter into a relationship with one. Even if she remained single her entire life, a lesbian would still experience lesbophobia and suffer from it. She would live in a world that erases her community and shames her for who she is. That would undoubtedly affect her sense of self and her well-being.

Likewise, even if she stays single or in heterosexual relationships her whole life, a bi or pan woman is also affected by lesbophobia, and she suffers from it too.

And this denial of the homophobia experienced by bisexual women continues even when they are in relationships with women.

Minimization of the Homophobia Experienced by Bi Women in Lesbian Relationships

Bisexual women are often confronted with a strange double standard. On one hand, they are told they do not face lesbophobia if they are single or in a heterosexual relationship. On the other hand, they are told they don’t truly experience lesbophobia even when they’re in a relationship with another woman. I’ve heard this second claim far too many times, often in subtle or indirect forms. In fact, the argument that biphobia doesn’t exist is often paired with a persistent, irrational idea: that bisexual women are somehow magically protected from lesbophobia.

Let me take the time to outline a few indirect ways in which the lesbophobia experienced by bi women in lesbian relationships is invalidated.

The first way is to exclude bisexual women from reclaiming stigmatized terms used to resist lesbophobic oppression.

On the internet, for instance, I have repeatedly been told not to use the word “gouine” (a reclaimed French dyke slur), supposedly because as a bi woman, I do not experience that form of oppression. I had used the term in a neutral, contextual way, referring to the differences between gouine (more underground) and lesbian (more institutional) cultures. My lesbian relationships were known to those involved in the discussion. Still, hostile commenters seemed to believe that this word could only be spoken by pure-blooded lesbians, as though my bisexuality protected me from the stigma that weighs on lesbian love.

But my bisexuality did not protect me from being hypervigilant in public spaces with every woman I ever dated. It did not stop a man from asking if I « licked my girl good at night » while trying to grope me and my partner. It didn’t stop that drunk guy from grabbing me and trying to kiss me by force to “tease my girlfriend.” It didn’t stop him from shouting “and don’t forget to f* real good” at us when we ran into him again. My bisexuality didn’t stop a harasser from calling me a “gouine” and a “pussy-eater.”

If being called a gouine makes one a gouine, then I am one, and so are many bisexual women.

The second way this oppression is minimized is more systematic and insidious: it’s done by downplaying the impact of lesbophobia during the relationship itself.

The same woman who once said her love for me exposed me to lesbophobia also claimed that, despite our relationship being public and official, I wasn’t really facing the same level of lesbophobia that she did as a lesbian, because we didn’t live together. Never mind that we had traveled to Spain so she could meet my family. That I had spoken of her and shown pictures of us to all my friends. That I had invited her to my workplace for a public event, and brought her to my colleague’s year-end gala. Apparently, because we didn’t share a home, that changed everything.

Strangely, she didn’t apply the same logic to herself, that not living with me meant she didn’t face lesbophobia either. When I pointed out how absurd that argument was, she doubled down. She told me that in any case, we would never go through IVF together, so I would never know what real lesbophobia was. According to her, as a bisexual woman, if I didn’t tick every box, living together, legal partnership, parenthood, I wasn’t entitled to claim victimhood. She, as a lesbian, had that right by birth.

This kind of hierarchization of lesbophobia, which my ex used to discredit my experience, is one of the mechanisms used to exclude bi women from lesbian solidarity. Lesbians are never subjected to this kind of gatekeeping. I’ve never heard anyone tell a lesbian that unless she goes through IVF, the lesbophobia she experiences isn’t legitimate. It is only bi women who are routinely placed on a spectrum of lesbianism, and who are forced to prove they’re oppressed enough to be taken seriously.

The Hierarchization of Lesbian Experience: A Tool of Biphobia

I’ve read and heard countless arguments along the same lines, arguments that place bisexual women within a logic of minimizing their homosexuality. One woman « wasn’t really queer » because she had never been in a serious relationship with a woman lasting more than six months… because her genitals had never been penetrated or licked by a woman… because she had never deep-kissed a woman, « just a peck, » so it didn’t count.

Clementine Morrigan, a bisexual Canadian writer, shares in an essay on betrayal how her first girlfriend, a teenage relationship, later described her as straight, disqualifying both their relationship and their sexual intimacy, because they had only orgasmed through grinding. That ex-girlfriend not only decided Morrigan wasn’t queer, but went out of her way to convince others of this years later (Morrigan, 2024).

Maybe you’re thinking there’s some threshold beyond which it becomes acceptable to deny a bisexual woman’s homosexuality and the lesbophobia she faces. Perhaps it would be too much to say I didn’t experience lesbophobia just because I didn’t go through IVF, but the woman who’s never deep-kissed another woman? That’s a different story…

But I don’t believe there’s any acceptable threshold for denying the very real lesbophobia bisexual women experience, or the homosexual nature of their desires and relationships. The moment a woman has felt « deviant » desire for another woman, she becomes vulnerable to lesbophobia.

I fully acknowledge that there’s a wide spectrum, from the terror of a first unfulfilled same-gender crush to the trauma of surviving a lesbophobic sexual assault in public. I’ve experienced both. But I also know that the gradient we’re forced into always aims to delegitimize bi women. This hierarchy is rarely about recognizing the severity of the most violent attacks. Those who insist on ranking us on a scale of victimhood have no real idea what the « least exposed » bisexuals live through, and always underestimate what the most exposed endure.

And a victim who is not recognized is a victim who is not defended. Victimhood is not a badge of honor, it’s the basis for collective defense. When that drunk man tried to kiss me by force, two women stepped in: my girlfriend, and a visibly queer waitress. She didn’t stop to ask whether I was bisexual or lesbian before stepping up. She simply recognized that I was experiencing a lesbophobic sexual assault in public, and acted out of solidarity.